Fateful Choices: Art from the Gurlitt Trove, a fascinating exhibit curated by Shlomit Steinberg, is on view at the Israel Museum until January 25th. Featured are close to 100 works from the cache of Hildebrand Gurlitt (1895-1956), whose collection passed to his son Cornelius (1932-2014). The collection, largely out of sight since the end of World War II, was discovered by chance in 2010, when the reclusive Cornelius Gurlitt, then in his seventies, was crossing the Swiss-German border by train. Discovered to have a large amount of cash on him, Gurlitt was subjected to a police investigation. Upon entering his home in Schwabing, a Munich borough, investigators came upon a large collection of art, comprising over 1500 pieces, mainly late 19th and 20th century, but not only. This discovery rocked the art world, especially those trying to locate art that had been confiscated or had otherwise disappeared in World War II. How did the Gurlitts wind up with this huge stash? That question is answered, at least partially, by the present exhibition.

There are three strands to this story. Hildebrand Gurlitt was an art historian and museum director turned art dealer under the Nazi Regime. As the director of an art museum in Zwickau (1925-1930), and then the Kunstverein in Hamburg (1931-1933), he started collecting modern German art. The rise of Nazism led to his dismissal from both posts because of this interest: the first in 1930, the second in 1933. However, the same hand that bit him later came to feed him. The Nazi obsession with art was two-pronged. On the one hand, the Nazis were fixated on getting rid of art works deemed unacceptable, or, as they were officially called, “Entartete Kunst” (“Degenerate Art”). This included not only the work of Jewish artists, such as Camille Pissarro, Max Liebermann and Marc Chagall, but also German artists of “Die Brücke”, like Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, as well as later members like Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein and Otto Mueller. Ironically, one of the artists the Nazis wanted removed from public collections was Franz Marc, of the Blau Reiter painters, who died defending Germany in World War I at Verdun. Thousands of works were confiscated from museums by a six-man commission established by Goebbel’s decree. The exhibit opened on July 19,1937 in Munich and then was shown in other venues all around Germany, and later Austria, until 1941. The Nazis were persuaded not to burn the works as they had originally intended, but to sell them abroad to raise much-needed foreign currency. One of the four dealers chosen for this task was Hildebrand Gurlitt. From their perspective, these dealers were not plundering art, but rather selling works from their country’s own collections for the good of the Fatherland. They would sell the works abroad, and receive their 10-20% commission in Reichsmarks.

The second thread of the story is that once Gurlitt was in the good graces of the Nazi art establishment, he became involved in fulfilling Hitler’s desire to acquire art for the museum Hitler was building in Linz, Austria. In this role, he bought art in France, some of which was from Jewish collections. Later, he was to claim in post-war investigations that he had no knowledge of the works’ provenance.

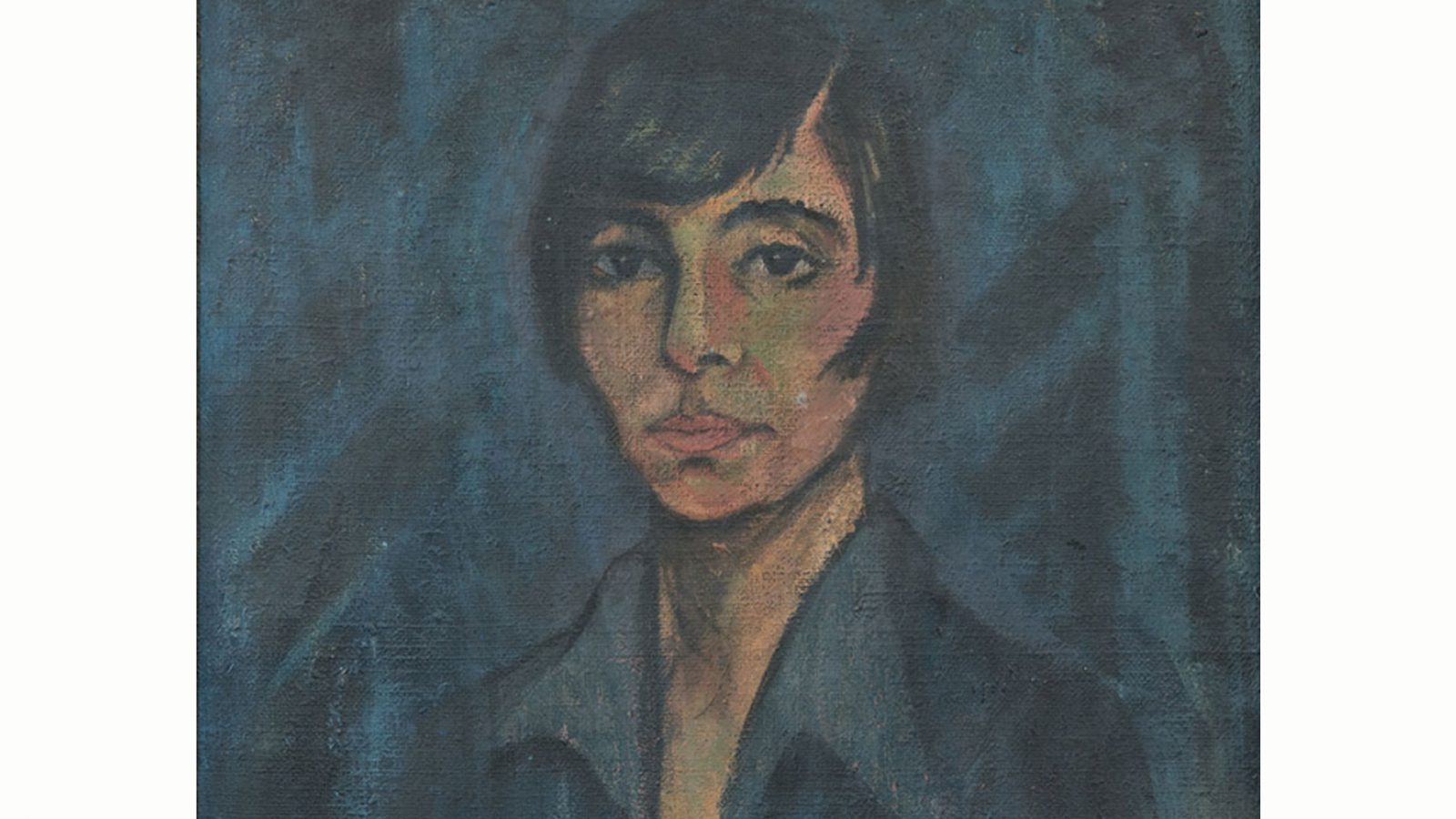

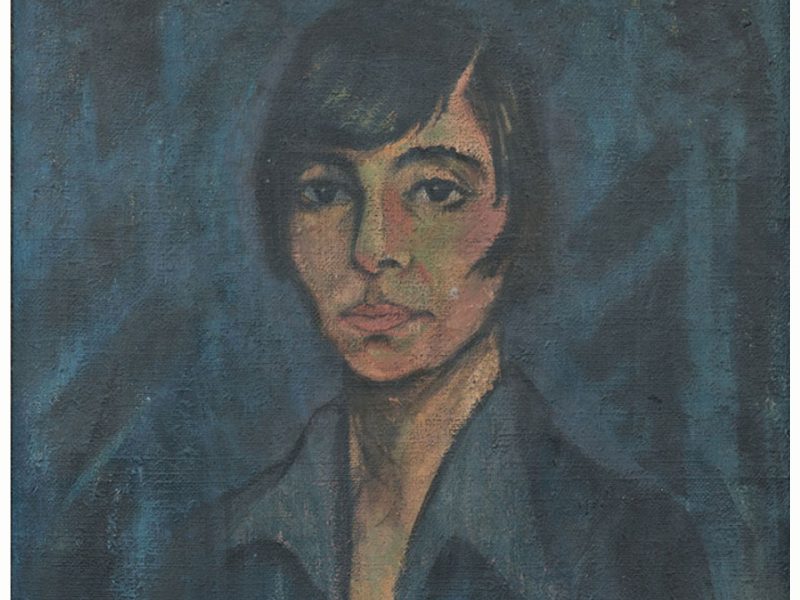

The third part of the story adds yet another level of complexity. Hildebrand Gurlitt came from a family of artists and art dealers: Gurlitt’s grandfather, Heinrich Louis Theodor Gurlitt (1812 – 1897) was a landscape painter; his father, Cornelius, an art dealer and published art historian, and his sister, Cornelia, an aspiring artist who put an end to her life in the wake of a failed love affair. His first cousin Wolfgang was also an art dealer.

Ironically, Gurlitt’s grandmother, Heinrich Louis’s third wife, was Elizabeth Lewald, from a prominent Jewish family. Elisabeth’s older sister Fanny Lewald (1811-1889) was a well-known writer and proto-feminist who converted to Christianity, and Elisabeth (apparently) followed suit. Despite their conversion, this family connection made Hildebrand Gurlitt one-quarter Jewish, or “Mischling zweiten Grades” (second-degree, half-caste). Thus, though Gurlitt’s family was not Jewish and moreover, even anti-Semitic, this Nazi category hung over their heads, and there is no doubt that Hildebrand’s brother Willebrand’s dismissal from his position as musicologist in 1937 heightened the family’s sense of precariousness. Gurlitt even took the precaution of registering his business in his wife’s name, since she was a complete “Aryan.” After the war, the Allies found Gurlitt and his collection hidden in a castle in Germany. In his post-war investigation by the Art Looting Intelligence Unit of the American Army in May 1945, Gurlitt claimed that he had feared for his life and that his business was a way to protect himself and his family during the war.

The exhibit is divided into three to reflect these threads.

The first part tells the story of the family and their art, and includes works by the grandfather and sister Cornelia. The second displays some of the works by German artists deemed “degenerate”, while the third showcases a potpourri of paintings, drawings and prints by artists such as Delacroix, Corot, Courbet, Manet, and Liebermann, as well as lesser-known artists. Most of the works in the trove have undergone thorough provenance research, the results of which are on-line for all to see, and also cited in the labels of each work. (A QR code on the label, linking to the eminently clear German website about the Gurlitt collection, might have saved visitors from bending to read the very fine print.)

Why see this exhibit?

First, one of the purposes of this exhibit, already shown in Bonn, Bern, and elsewhere, is to bring this artwork into the public eye, in the hope that justice may in some small way be served. Indeed, just this week a family was able to recover some of their works from the collection, as reported by Forbes. According to the website, some 315 works were most likely taken from museum collections, and another 724 have been investigated. Of those, 640 have gaps in their provenance, yet only four are known for sure to be looted art. Secondly, the exhibit allows one to view art that was confiscated by the Nazis and deemed “degenerate”. Lastly, by viewing the other works, by and large not well-known, one gets a sense of the artistic taste of private collectors pre-World War II, among them probably many Jewish collectors. These works are a stand-in for those families that were unable to claim their works at the end of the war, and by visiting this collection, we honor their memories.